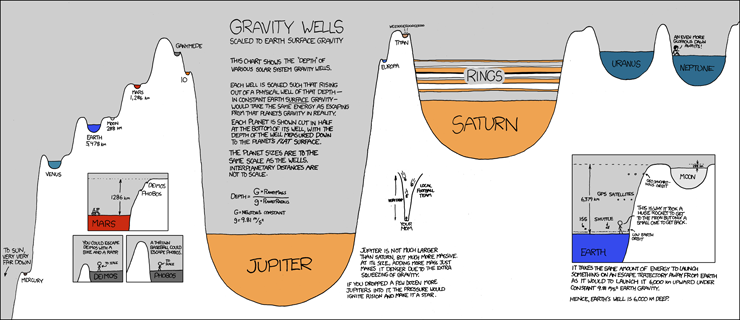

This latest offering from Randall Munroe is a thing of joy.

`Do Mages often beg?' asled Tenar, on the road between green fields, where goats and little spotted cattle grazed.Ursula K. Le Guin, The Tombs of Atuan, 1971

`Why do you ask?'

`You seemed used to begging. In fact you were good at it.'

`Well, yes. I've begged all my life, if you look at it that way. Wizards don't own much, you know. In fact nothing but their staff and clothing, if they wander. They are received and given food and shelter, by most people, gladly. They do make some return.'

`What return?'

`Well, that woman in the village. I cured her goats.'

`What was wrong with them?'

`They both had infected udders. I used to herd goats when I was a boy.'

`Did you tell her you'd cured them?'

`No. How could I? Why should I?'

After a pause she said, `I see your magic is not good only for large things.'

`Hospitality,' he said, `kindness to a stranger, that's a very large thing. Thanks are enough, of course. But I was sorry for the goats.'

`The thief who wrote the way to enter thought that the treasure was there, in the Undertomb. So I looked there, but I had the feeling that it must be better hidden farther on in the maze. I knew the entrance to the Labyrinth, and when I saw you, I went to it, thinking to hide in the maze and search it. That was a mistake, of course. The Nameless Ones had hold of me already, bewildering my mind. And since then I have grown only weaker and stupider. One must not submit to them, one must resist, keep one's spirits always strong and certain. I learned that a long time ago. But it's hard to do, here, where they are so strong. They are not gods, Tenar. But they are stronger than any man.'Ursula K. Le Guin, The Tombs of Atuan, 1971

They were both silent for a long time.

`What else did you find in the treasure chests?' she asked dully.

`Rubbish. Gold, jewels, crowns, swords. Nothing to which any man alive has any claim ...'

She wanted no more talk of Erreth-Akbe, sensing a danger in the subject. `He was a dragonlord, they say. And you say you're one. Tell me, what is a dragonlord?'Ursula K. Le Guin, The Tombs of Atuan, 1971

Her tone was always jeering, his answers direct and plain, as if he took her questions in good faith.

`One whom the dragons will speak with,' he said, `that is a dragonlord, or at least that is the centre of the matter. It's not a trick of mastering the dragons, as most people think. Dragons have no masters. The question is always the same, with a dragon: will he talk with you or will he eat you? If you can count upon his doing the former, and not doing the latter, why then you're a dragonlord.'

`Dragons can speak?'

`Surely! In the Eldest Tongue, the language we men learn so hard and use so brokenly, to make our spells of magic and of patterning. No man knows all that language, or a tenth of it. He has not time to learn it. But dragons live a thousand years ... They are worth talking to, as you might guess.'

The machinist climbs his ferris wheel like a brave,Wild Billy's Circus Story is the fourth track on The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, Bruce Springsteen's second album. Released thirty-six years ago today, just eight months after his astonishing debut, it's still one of his best albums: it has the madcap zest of Asbury Park, but more discipline; more poetry.

And the fire-eater's lying in a pool of sweat, victim of the heatwave,

Behind the tent, the hired hand tightens his legs

on the sword-swallower's blade —

Circus town's on the shortwave.

Well the runway lies ahead like a great false dawn,

Fat Lady, Big Mama, Miss Bimbo sits in her chair and yawns,

And the Man-Beast lies in his cage, sniffing popcorn,

As the midget licks his fingers, and suffers Missy Bimbo's scorn —

And circus town's been born.

Oh and a press roll drummer goes ballerina to and fro,

Cartwheeling up on that tightrope,

With a cannon-blast, lightning-flash,

Moving fast through the tent, Mars-bent,

He's going to miss his fall —

Oh God save the human cannonball!

And the Flying Zambinis watch Marguarita do her neck-twist,

And the ringmaster gets the crowd to count along:

Ninety-five, ninety-six, ninety-seven ...

A ragged suitcase in his hand,

he steals silently away from the circus-ground,

And the highway is haunted by the carnival sounds:

They dance like a great greasepaint ghost on the wind ...

A man in baggy pants, a lonely face, a crazy grin,

Running home to some small Ohio town:

Jesus send some good women to save all your clowns ...

And the circus-boy dances like a monkey on barbed wire,

As the barker romances with a junkie, she's got a flat tire,

And the elephants dance real funky,

and the band plays like a jungle fire —

Circus town's on the live wire —

And the Strong Man Samson lifts the midget little Tiny Tim

way up on his shoulders — way up! —

And carries him home down the midway:

Past the kids,

Past the sailors,

To his dimly lit trailer;

And the ferris wheel turns and turns like it ain't ever going to stop,

And the circus-boss leans over and whispers in the little boy's ear,

“Hey son, you want to try the Big Top?

All aboard! Nebraska's our next stop.”

Ged had taken hawk-shape in fierce distress and rage, and when he flew from Osskill there had been but one thought in his mind: to outfly both Stone and shadow, to escape the cold treacherous lands, to go home. The falcon's anger and wildness were like his own, and had become his own, and his will to fly had become the falcon's will. Thus he had passed over Enlad, stooping down to drink at a lonely forest pool, but on the wing again at once, driven by fear of the shadow that came behind him. So he had crossed the great sea-lane called the Jaws of Enlad, and gone on and on, east by south, the hills of Oranéa faint to his right and the hills of Andrad fainter to his left, and before him only the sea; until at last, ahead, there rose up out of the waves one unchanging wave, towering always higher, the white peak of Gont. In all the sunlight and the dark of that great flight he had worn the falcon's wings, and looked through the falcon's eyes, and forgetting his own thoughts he had known at last only what the falcon knows; hunger, the wind, the way he flies.Ursula K. Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea, 1968.

He flew to the right haven. There were few on Roke and only one on Gont who could have made him back into a man.

It sounds paradoxical to link the desire for unlimited medical treatment to the desire for physician-assisted suicide. But the idea that there’s a right to the most expensive health care while you want to be alive isn’t all that different, in a sense, from the idea that there’s a right to swiftly die once life doesn’t seem worth living.Ross Douthat on physician-assisted suicide and the American polity.

In each case, the goal is perfect autonomy, perfect control, and absolute freedom of choice. And in each case, the alternative approach — one that emphasizes the limits of human agency, and the importance of humility in the face of death’s mysteries — doesn’t mesh with our national DNA.

More than most Westerners, Americans believe — deeply, madly, truly — in the sanctity of marriage. But we also have some of the most liberal divorce laws in the developed world, and one of the highest divorce rates. We sentimentalize the family, but boast one of the highest rates of unwed births. We’re more pro-life than Europeans, but we tolerate a much more permissive abortion regime than countries like Germany or France. We wring our hands over stem cell research, but our fertility clinics are among the least regulated in the world.Concerning that permissive abortion regime, there's this over at First Things:

In other words, we’re conservative right up until the moment that it costs us...

Prior to the legalization of abortion in the United States, it was commonly understood that a man should offer a woman marriage in case of pregnancy, and many did so. But with the legalization of abortion, men started to feel that they were not responsible for the birth of children and consequently not under any obligation to marry. In gaining the option of abortion, many women have lost the option of marriage. Liberal abortion laws have thus considerably increased the number of families headed by a single mother, resulting in what some economists call the “feminization of poverty.”(From Richard Stith's Her Choice, Her Problem: How Abortion Empowers Men.) Back at the Times, RD muses on how the issue might have played differently, if Ted Kennedy had shared some of his sister Eunice's qualms about the practice.

No creature moved nor voice spoke for a long while on the island, but only the waves beat loudly on the shore. Then Ged was aware that the highest tower slowly changed its shape, bulging out on one side as if it grew an arm. He feared dragon-magic, for old dragons are very powerful and guileful in a sorcery like and unlike the sorcery of men: but a moment more and he saw this was no trick of the dragon, but of his own eyes. What he had taken for a part of the tower was the shoulder of the Dragon Pendor as he uncurled his bulk and lifted himself slowly up.Ursula K. Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea, 1968.

When he was all afoot his scaled head, spike-crowned and triple-tongued, rose higher than the broken tower's height, and his taloned forefeet rested on the rubble of the town below. His scales were grey-black, catching the daylight like broken stone. Lean as a hound he was and huge as a hill. Ged stared in awe. There was no song or tale could prepare the mind for this sight. Almost he stared into the dragon's eyes and was caught, for one cannot look into a dragon's eyes. He glanced away from the oily green gaze that watched him, and held up before him his staff, that looked now like a splinter, like a twig.

`Eight sons I had, little wizard,' said the great dry voice of the dragon. `Five died, one dies: enough. You will not win my hoard by killing them.'

`I do not want your hoard.'

The yellow smoke hissed from the dragon's nostrils: that was his laughter.

`Would you not like to come ashore and look at it, little wizard? It is worth looking at.'

`No, dragon.' The kinship of dragons is with wind and fire, and they do not fight willingly over the sea. That had been Ged's advantage so far and he kept it; but the strip of seawater between him and the great grey talons did not seem much of an advantage, any more.

It was hard not to look into the green, watching eyes.

When a man's ways please the Lord, the Scriptures tell us, He maketh even his enemies to be at peace with him.

— Proverbs 16:7

What sort of judgment was the community social worker making when he swore the stepfather was a nice feller? Was he frightened of the man? That was possible; but more likely he wanted to be his mate. The young social workers of the time, coming up through university courses – postgraduate training after a sociology degree – thought it a sin to be judgmental. In fact they were making judgments all the time. Uneasy about their own middle-class backgrounds, and always feeling vaguely uncool, they believed they should not ‘label’ clients or assess ‘working-class’ people by their own middle-class criteria; so they treated them as if they were dogs and cats, not responsible for their actions. They had a whole set of interesting beliefs about the uneducated and the poor. They didn’t see that they were being grossly condescending, while pretending to be the opposite. Aspiration was a middle-class trait, they thought; the working classes preferred to muddle along. The privileged had their ethical standards, but it was unfair to universalise them. The workers had their own amusements, bless them, and should be allowed their vices. Their houses were dirty, but it was petty bourgeois to worry about grime. And if they were drunken or semi-criminal, and beat each other, wasn’t that their culture? These young graduates took as typical the malfunctioning families with whom their case files brought them into contact. Worse, they wanted their clients to like them. They dressed in recidivist chic and roughed up their accents. Their heads were full of Durkheim, their mouths full of glottal stops. They were occupied in creating a moral vacuum; theirs was a world safe for theory but profoundly unsafe for any child who needed them to shape up and go to work.Hilary Mantel, from a brief memoir of her time as a social work assistant, in an issue of the London Review of Books from earlier this year.

I wrote down the details of Ruby’s case and put it in the files. Soon after, I left my job. The chest hospital closed its doors in 1982 and, the National Archives says, ‘no records are known to survive.’ I don’t know the end of the story...

Second, the United States needs to develop clearly articulated standards for its relations with the nondemocratic world. Our distinct policies toward different countries amount to a form of situational ethics that does not translate well into clear-headed diplomacy. We must talk to Myanmar’s leaders. This does not mean that we should abandon our aspirations for a free and open Burmese society, but that our goal will be achieved only through a different course of action...US Senator Jim Webb, following his return from Burma, in an op-ed entitled “We Can’t Afford to Ignore Myanmar”. I suspect this is right as far as it goes, but our public discourse on democracy and rights has become so strident, and so little thought-through — while in many other respects, business goes on as usual — that's it's become hard to imagine what a more consistent approach would actually look like.

Third, our government leaders should call on China to end its silence about the situation in Myanmar, and to act responsibly, in keeping with its role as an ascending world power. Americans should not hold their collective breaths that China will give up the huge strategic advantage it has gained as a result of our current policies. But such a gesture from our government would hold far more sway in world opinion than has the repeated but predictable condemnation of Myanmar’s military government...

This has not, obviously, been a book of apologetics, in large part because I still find myself less perturbed by the sanctimonious condescension of many of those who do not believe than by either the gelid dispassion or the shapeless sentimentality of certain of those who do. Neither has it been a book of “technical” or “philosophical” theology, though I have at points touched upon “technical” elements of Christian philosophical tradition (too lightly, I fear, to be entirely convincing and too heavily to be entirely lucid). Much less has it been a book of consolations. Rather, my principal aim has simply been to elucidate — as far as in me lies — what I understand to be the true scriptural account of God's goodness, the shape of redemption, the nature of evil, and the conditions of a fallen world, not to convince anyone of its credibility, but simply to show where many of the arguments of Christianity's antagonists and champions alike fail to address what is most essential to the gospel.From the conclusion of D.B. Hart's The Doors of the Sea.

Healthy, natural systems abhor uniformity — just as a healthy society does. We need, then, to look to a system of food and agriculture that values and mimics natural diversity. The five-acre monoculture of tomato plants next door might be local, but it’s really no different from the 200-acre one across the country: both have sacrificed the ecological insurance that comes with biodiversity.

What does the resilient farm of the future look like? I saw it the other day. The farmer was growing 30 or so different crops, with several varieties of the same vegetable. Some were heirloom varieties, many weren’t. He showed me where he had pulled out his late blight-infected tomato plants and replaced them with beans and an extra crop of Brussels sprouts for the fall. He won’t make the same profit as he would have from the tomato harvest, but he wasn’t complaining, either...

For this reason, the atheist who cannot believe for moral reasons does honor, in an elliptical way, to the Christian God, and so must not be ignored. He demands of us not the surrender of our beliefs but a meticulous recollection on our parts of what those beliefs are, and a definition of divine love that has at least the moral rigor of principled unbelief. This, it turns out, is no simple thing. For sometimes atheism seems to retain elements of “Christianity” within itself that Christians have all too frequently forgotten.This from David Bentley Hart's 2005 essay The Doors of the Sea: Where Was God in the Tsunami? which I belatedly read today; various friends have been recommending Hart to me over the last few years — I especially enjoyed his recent reflection on Edward Upward — and it seemed high time to read his celebrated rebuke of theodicy. It's very much written to a Christian audience, and largely concerned with inept and offensive positions held by Christians, but it would be of interest and benefit to at least some other people interested in these issues.

The question — and I have struggled with this myself — is where do you have the most impact, where do you drive most effectively. It is always changing as the world changes. I used to humiliate CEOs, and one needed to be sufficiently emotionally unaware to live with that ethical contradiction — of making leaders look bad in order to get your point across.So Paul Gilding, former Greenpeace director, as quoted in an article about the Australian singer-turned-politician Peter Garrett [in the SMH's Good Weekend, apparently not online]. It's worth a read, although it's not always so ethically aware: the journalist wants to have his cake and eat it too, issuing cheap shots against Garrett at one remove, or maybe half a remove. The smarmiest of Garrett's critics is Bob Brown, head of the Greens, who has quite a line in moral one-upmanship. Here's a hint, Bob: if you have a former colleage, whom (as you say) you like a great deal, and feel empathy for, and yet you find yourself feeling "a great deal of anxiety for him as a person", pick up the phone, or walk down the corridor to his office, and talk to him personally. Keep your pious concerns out of the press. Or, you know, we might think it had more to do with establishing your own brand by trashing a professional rival.

And I think that's the crux of this, you know, `Peter Garrett is not the person he was before. He's become a politician.' Well, yeah, that's right. I did become a politician and I made that step into the discipline of party politics.Garrett, currently Minister for the Environment, Arts and Heritage, is — and I didn't know this — the second-oldest member of cabinet, which is a disorienting thought. And how he has ever been able to make it through the song Beds Are Burning, given his personal history, boggles the mind.

Collette is impressively convincing, even though I’m not entirely sure what I’m being convinced of.

A Sarah Palin who stepped down for the sake of her family and her media-swarmed state deserves sympathy even from the millions of Americans who despise her. A Sarah Palin who resigned in the delusional belief that it would give her a better shot at the presidency in 2012 warrants no such kindness.Over the last few months I have been enjoying the columns of Ross Douthat, the New York Times' new resident conservative: to give a recent selection, here he is offering a critical take on the US Supreme Court, and on using the Constitution to regulate abortion; giving a sane synopsis of where things stand for America in Iraq; and asserting that the basis of affirmative action (if any) will have to shift from race to class.

Either way, though, her 10 months on the national stage have been a dispiriting period for American democracy.

If Palin were exactly what her critics believe she is — the distillation of every right-wing pathology, from anti-intellectualism to apocalyptic Christianity — then she wouldn’t be a terribly interesting figure. But this caricature has always missed the point of the Alaska governor’s appeal ...

When we talked about the first reality programs, years ago, we worried about obvious things: that in the environment of these shows, things would be broken that could not be fixed; that sooner or later, someone was going to be raped, or badly hurt; that some already-damaged person might be destroyed. The genius of Series 7 is to see that this was never really the point. The literal horror is taken for granted, and it's sadly true that it doesn't revolt as much as it “should”: people are killed all through this program, but with the exception of a particular lethal beating, none of it makes you wince. But one winces every moment at the loss of shame, of self-respect, and of any kind of restraint, not just by the contenders, but by the relentless, sententious voice-over, and the public that it's co-opted to its perspective.From my review of the film Series 7, posted over at my Bruce's Reviews side-project. Enough has been said about “reality” radio in Sydney in recent days, but what's saddest is that it took a severe incident involving a child to get the show pulled. As if the basic premise, and the general behaviour of the show, were not bad enough. It put me in mind of a distant time when deliberately contrived dysfunction was still felt as an innovation, and could offend just by being itself. I wrote the review in '03, of an '01 film; the first stabs at reality radio and television in the nineties were still fresh in memory. But as of this writing, children who were born in that period are in high school, and have known no other world.

The reason to turn off the porn might become, to thoughtful people, not a moral one but, in a way, a physical- and emotional-health one; you might want to rethink your constant access to porn in the same way that, if you want to be an athlete, you rethink your smoking. The evidence is in: Greater supply of the stimulant equals diminished capacity.The tacit assumption here is that moral arguments, and physical- and emotional-health arguments, are separate: that the proposition, “that porn damages people's ability to form and sustain healthy relationships”, is somehow irrelevant to the moral status of the thing. But this is unreal. Moral thought, amongst other things, is about integration; and it is most certainly about the real world.

After all, pornography works in the most basic of ways on the brain: It is Pavlovian...

Professor, you've chosen the metaphor of wakefulness, and of the future that presents itself to you for you for your action or decision, rather than the metaphor of “making decisions”. Which made me think about making decisions. There's this lovely phrase about “creeping non-choice”: how did you come to be in this situation, did you choose it? Well no, it was a kind of creeping non-choice. So, reflecting on the past, for ten years I was never aware of making any particular choice, but I look back on where I was and where I stand, and I find that I have made a choice, I have made a decision. So, given that you're speaking in terms of the future that presents itself to you for action, do you want to say something about discerning what the choices for action actually are, and how you see that?This from Oliver O'Donovan's 2007 New College Lectures, in response to my question. Of course I was invoking (not particularly clearly) the famous saying re involuntary childlessness in our culture: something that outsiders may consider a “choice”, but that the person concerned does not experience that way.

Yes, yes. And I will say more — this gives me an opportunity to offer a trailer for the third lecture, which I'm very content to do, because this is a matter to which I want to attend more fully on Thursday night. I will consider there a model of making decisions and what they are, which is, as it were, the apple-and-pear model: in my left hand I have an apple, in my right hand I have a pear, and I am in a dilemma because I don't know which to bite into. And there is one understanding of moral decision which understands it always in terms of a kind of “either-or”. I always stand before two ways: two commendable paths, and I have to choose one or the other. I don't think that's a very good model for making decisions, and I want to suggest that our process in reaching decisions is one of increasing clarification: increasing understanding of ourselves, which is far more like bringing something more and more into focus. So, we start with a very blurred picture, a very vague large-scale map of what it is that lies before us, and as we go we are constantly trying to sharpen the focus, to see more detail, until the picture of what is before us and what we can do becomes sharp.

I think that when we make a decision, and particularly our very best decisions, is the moment in which we realise we don't any longer have an alternative. It's not the moment in which we realise that we have two absolutely equal alternatives, and it's absolutely up to our choice as to which we take.

To take an example of this—as I don't include this in the third lecture, I might as well include it now—I remember one occasion, in which I was on one of those committees that universities throw up from time to time, with the duty of appointing a professor to a post. And before the committee had met, a colleague met me in the street and said, “I hear you're on that committee to appoint the chair of such-and-such: You will, of course, appoint Professor Jones.” And I said, “Well, will we?”. “Well, yes,” he said, “you will.” Several months later we appointed Professor Jones. The process had been a very long one. We had naturally looked at some excellent CVs. We had considered a wide variety of alternatives. But what got borne in on us in that whole process, was what was obvious to my colleague from the beginning, namely that Professor Jones was the person who ought to be appointed to that chair.

One doesn't regret that situation, one doesn't say, “Oh this is a terrible situation, here is an outstanding candidate, I have no choice, I have no decision to make.” The decision is recognising the outstanding candidate, hmm? That's what deciding is. Now I think that's a better model for most of our decisions than apples and pears: shall I eat an apple or shall I eat a pear, there's nothing to choose, I'm going to toss a coin, and so on.

You gave a fairly prominent place to compromise in this evening's lecture—twinned together, I thought very helpfully, with ideals. On my reading, compromise enjoys a dreadful reputation in the Christian community at the moment. And you're also emphasising the need to act together, or with one mind—whereas I picture myself in a room with my brothers and sisters, recommending some course of action, that could be described as a compromise, let alone myself describing it as a compromise, and this seems like the political equivalent of suicide within the community. Are these just the times that we live in? Do you agree with that reading, or is there some way forward from this? Because, as I say, I think compromise has a very bad name, but I agree with you it's necessary, so ...This from Oliver O'Donovan's 2007 New College Lectures, Morally awake? Admiration and resolution in the light of Christian faith, in response to my question.

Thank you for that question, which is rather searching. I'm not sure that I can do more than kind of feel after an answer to it...

I think we distrust compromise because we associate it with a certain kind of temptation, which is a temptation to fall in with what everybody else is doing. To being conformed to this world, as St Paul puts it. That seems to me to be, as a phrase, perfect for summing up the nature of the bad compromise. [We are] rightly concerned about that: rightly on guard against any such concession, and of course, as we all know, it's ferociously easy, even for the most serious-minded of us, simply to fall in with the way other people do things, because it takes so much less effort, and our effort is being seriously required for other tasks ...

We fail to see ... as it were, the other kind of compromise, which perhaps ... perhaps it's a bad thing that we end up with the same word to describe two things, except when words are ambiguous, they warn us against certain very easy mistakes, and the fact that "compromise" is used both, as it were for the good [compromise, the] trying-to-focus-on-the-sheerly-practical-in-the-situation, the actually-bringing-into-shape of what it is that we really can do that will bear witness to God's command and to the object set before us, and [also for the bad compromise:] failing to do this because we fall in with everyone else, warns us that it's easy to mistake the one for the other, and it's easy to mistake the one for the other because discerning what is actually practicable is difficult. And we may think that because everybody disagrees with a course of action that we think right, therefore that course of action is not practicable. And that's one reason why the two types of compromise are so necessary to keep clear.

The question we have to ask is what is the best course of action that is actually available. And both sides of that equation have to be brought together. If we do that, and if we regularly did that, then compromise could lose its bad reputation perhaps.

Sympathy is Crowe's great gift, but it's a kind of weakness as well. He has rightly been criticised for the lack of darkness in his films, and there's clearly no question of them holding up a mirror to all of life. Yet with Lloyd, at least, there's an element of mystery: we have no idea of his relationship with his (absent) parents; his aimlessness hints at trouble ahead. And there's something between confusion and anger that underlies his riffs in conversation, which Crowe and Cusack are wise enough to merely suggest—it's never discussed. It would also seem to undergird his awe of Diane, who is more at peace with herself. When the couple split Lloyd is all at sea, swinging between shattered grief and self-conscious poses of defiance. Whereas Diane, while miserable, still has her prospects and her father ... or so she thinks.This from my 2002 review of Say Anything ..., which I have rescued from its web oblivion and posted at Bruce's Reviews for the 19th anniversary of the film's release.

Really, “Away We Go” is about the flight from adulthood, from engagement, from responsibility, even as it cleverly disguises itself as a search for all those things. But the dream of being left alone in a world of your own making, far from anything sad or icky or difficult, is a child’s fantasy.Stirring stuff. Likewise concerning topics on which it is difficult to talk sensibly, or well, consider the following:

It has been 16 years, in fact, since another young, freshly inaugurated Democratic president with a Democratic Congress tried to remake the architecture of health care, and the catastrophe that followed is generally cited as the main deterrent to thinking big about anything in the capital. The plan Bill Clinton took to Congress then, running to more than 1,000 pages of impenetrable new regulations, wasn’t what you’d call politically savvy, but the strategy used to sell it was even worse. Having been elected as the latest in a series of outsider presidents after Watergate, ex-Governor Clinton seemed to believe he had been sent by the voters to purify the fetid culture of Washington; he installed a boyhood friend as his chief of staff and stocked his White House with loyal Arkansans and campaign aides ready to overrun a fossilized Congress. His wife, the current secretary of state, developed the health care plan largely without taking House and Senate leaders into her confidence, instead dropping it at the doorstep of the Capitol as a fait accompli. Ever jealous of its prerogative, Congress took a long look, yawned and kicked the whole plan to the gutter, where it soon washed away for good — along with much of Clinton’s ambition for his presidency.How people continue to regard Obama as a pushover and a mere talker escapes me.

The first senator elected directly to the Oval Office since 1960, Obama has an entirely different theory of how to exercise presidential power, and he has consciously designed his administration to avoid Clinton’s fate. After winning the office with the same kind of outsider appeal as his predecessors, he has quietly but methodically assembled the most Congress-centric administration in modern history ... Obama seems to think that the dysfunction in Washington isn’t only about the heightened enmity between the parties; it’s also about the longstanding mistrust between the two branches of government that stare each other down from twin peaks on either end of Pennsylvania Avenue.

Governments typically make several mistakes when attempting to separate violent extremists from populations in which they hide. First, they often overestimate the degree to which a population harboring an armed actor can influence that actor’s behavior. People don’t tolerate extremists in their midst because they like them, but rather because the extremists intimidate them. Breaking the power of extremists means removing their power to intimidate — something that strikes cannot do...

The lack of oversight, and of targets, must send a chill of horror through any modern manager of a school, and with some reason: it was pretty haphazard, and who was to say that only good teaching would or did come of the laissez-faire system? The line between liberty and libertarianism is very indistinct, and the desire to dismantle bureaucracy and social inequity leaves open the possibility of chaos, and creates endless opportunities for individual self-aggrandisement. But it seems to me that the risks were worth taking, now that we've seen the dismal results of our 20-year-long experiments with centralised targets, management echelons and paper-based accountability.

I've called this story a “myth”, not in the vulgar sense that “it didn't really happen”, but in the more technical sense that it's part of the way we think: a story we tell to explain the way the world is, to position ourselves politically and socially, to understand what kinds of action are possible or desirable, and why. The modern myth is a defiantly unfair reading of Genesis 3, which is part of the point of it: it's an alternative vision of the world.This from my 2001-02 review of the film Pleasantville, which has been living in an obscure part of the web for years; it's now been uploaded to my new blog of the same name, Bruce's Reviews. More to come over the next little while.

And this is where Pleasantville comes in. The visitors from the 90s bring colour to the world around them, Jennifer by introducing the locals to the life of the body, David (after initial resistance) by opening up the life of the mind ... but they themselves remain stubbornly monochrome. Jennifer is puzzled ...

A view of the planet Neptune, and its giant moon Triton, from a distance of 3.75 billion kilometres, taken by the New Horizons spacecraft, en route to the dwarf planet Pluto and the Kuiper Belt. Image details can be found on this page at the NH website.

A view of the planet Neptune, and its giant moon Triton, from a distance of 3.75 billion kilometres, taken by the New Horizons spacecraft, en route to the dwarf planet Pluto and the Kuiper Belt. Image details can be found on this page at the NH website.The best counterargument is the same as the best counterargument on all gay-marriage topics: “This isn’t just about gay marriage but about a whole panoply of prior changes, most of which have obvious good qualities as well, so you’re not seeking status quo so much as rollback.” ...Her other comments ad loc are incisive, quite wide-ranging, and well-taken; and some of the links are fascinating. At the end of the day, though, I'm still confused about how she can reconcile herself to a group running an ad that she herself describes as fearmongering, and as “really, really cheesy”.

I see the force of that argument, and of course I acknowledge that there’s no way we would be having this conversation without the prior cultural changes which led to e.g. laws against discrimination based on sexual orientation. For that matter, every single day I take advantage of the cultural changes which have made it possible for me to be an out lesbian while facing very limited explicit hostility.

But I still disagree that gay marriage is only a trivial turn of the ratchet (do ratchets turn?? I’m really not the home-improvement kind of dykey!), a mere formality, or something you can only worry about if you also reject all of the prior cultural moves which brought us here. I think prudence can allow you to draw a line, and frankly, gay marriage is a really obvious place for that line. Gay marriage is a big deal for the same reasons given by its supporters!--it is a real change in the culture, a deeply significant change, and a change with far-reaching public implications. I don’t think you can write paeans to marriage as a public and cultural status, then turn around and say that gay marriage will have very limited public effects. Marriage isn’t designed to have limited public effects.

[following the model of] Teach for America, which harnesses the energy of college graduates who are willing to give a little time before moving to the next stage of their careers... Research for America could serve a similar purpose of giving smart young people a chance to see if research is the right career for them, without committing five or more years to getting a postgraduate degree.The writers have specifically biomedical research in mind, and (obviously) are thinking about the American situation. That said, they have at least addressed what seems to be a general problem with research at the moment: it needs a lot of workers, far more than can go on to full-fledged research careers of their own, so the academic system of apprenticeship-by-research-degree-and-postdoctoral-work strains to accomodate them. As a result we either create expectations that cannot be met, or damage the apprenticeship system for those that still truly need it, or both ...

Using as few hypothetical laws as possible, science attempts to explain relations between observable facts, arriving at them in a deductive manner, that is, in a purely logical way. Physics is customarily referred to as an empirical science and it is believed that its fundamental laws are deduced from experiments, so as to indicate how it differs from speculative philosophy. However, in truth the relationship between fundamental laws and facts from experience is not that simple. Indeed, there is no scientific method to deduce inductively these fundamental laws from experimental data. The formulation of a fundamental law is, rather, an act of intuition which can be achieved only by one who watches empirically with the necessary attention and has sufficient empirical understanding of the field in question. The sole criteria for the truth of a fundamental law is only that we can be sure that the relations between observable events can be logically deduced from it. It follows then that a fundamental law can be refuted in a definite manner, but can never be definitely shown to be correct, as one must always bear in mind the possibility of discovering a new phenomenon that contradicts the logical conclusions arising from a fundamental law.Albert Einstein, Unpublished Opening Lecture for the Course on the Theory of Relativity in Argentina, 1925

Experience is, therefore, the judge, but not the generator of fundamental laws. The transition from the facts of experience to a fundamental law often requires an act of free creativity from our imagination, as well as an act of creation of concepts and relations; it would not be possible to replace this act with a necessary and conclusive method...

The loss of a sense of appropriate time is a major cultural development, which necessarily changes how we think about trust and relationship. Trust is learned gradually, rather than being automatically deliverable according to a set of static conditions laid down. It involves a degree of human judgement, which in turn involves a level of awareness of one's own human character and that of others – a degree of literacy about the signals of trustworthiness; a shared culture of understanding what is said and done in a human society. And this learning entails unavoidable insecurity... And the further away I get from these areas of learning by trial and error, the further away I get from the inevitable risks of living in a material and limited world, the more easily can I persuade myself that I am after all in control.On risk and capitalism:

Although people have spoken of greed as the source of our current problems, I suspect that it goes deeper...

Ethical behaviour is behaviour that respects what is at risk in the life of another and works on behalf of the other's need. To be an ethical agent is thus to be aware of human frailty, material and mental; and so, by extension, it is to be aware of your own frailty. And for a specifically Christian ethic, the duty of care for the neighbour as for oneself is bound up with the injunction to forgive as one hopes to be forgiven; basic to this whole perspective is the recognition both that I may fail or be wounded and that I may be guilty of error and damage to another.and on embodiment:

It's a bit of a paradox, then, to realise that aspects of capitalism are in their origin very profoundly ethical in the sense I've just outlined. The venture capitalism of the early modern period expressed something of the sense of risk by limiting liability and sharing profit ...

One of the things most fatal to the sustaining of an ethical perspective on any area of human life, not just economics, is the fantasy that we are not really part of a material order – that we are essentially will or craving, for which the body is a useful organ for fulfilling the purposes of the all-powerful will, rather than being the organ of our connection with the rest of the world. It's been said often enough but it bears repeating, that in some ways – so far from being a materialist culture, we are a culture that is resentful about material reality, hungry for anything and everything that distances us from the constraints of being a physical animal subject to temporal processes, to uncontrollable changes and to sheer accident.